As the cost of plugging the gap under the St Clair sea wall spirals past $300,000, Debbie Porteous' thoughts turn to sand.

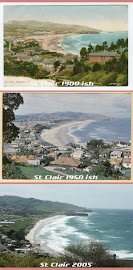

When the new sea wall was built in front of the old one at St Clair in 2004, a lot of people said something also had to be built to protect it.

After years of increasing beach scouring, the eventual exposure of its toe and inevitable sink-holes in the footpath above in the late 1990s, there were many warnings from experts.

The warnings were that wave pressure and sand erosion at St Clair Beach needed somehow to be mitigated or the wall, and the beach, would take a beating.

They were accompanied by high level of concern from the community.

Every person agreed that when waves reflected off the wall they scoured the beach.

As the beach became lower the waves could reach the wall more easily, smacking into it harder and scouring more and more sand from its front.

Contractors work on the last section of sheet piling going in in front of the sea wall to stop it being undermined.

Sand moved to and fro, but it was clear it was not returning at the rate it was leaving.

Canterbury University engineering dean Prof Alex Sutherland warned that without mitigation, the vertical sea wall would continue to lower the beach level.

The Dunedin City Council's consultant engineers said a breakwater was needed to break waves offshore and create a reservoir of sand at the beach.

A Otago Regional Council hearings panel - despite turning down consent to build a breakwater - suggested the city council investigate options to mitigate waves hitting the wall and beach scouring.

''... and a longer-term management strategy to address these effects as far as is reasonably practicable.''

Members of the public welcomed a new wall, but said it should be only the first step in protecting the area.

It was the appearance of sinkholes in the Esplanade - not unlike those that have appeared there now - and the exposure of the original wall's foundations in the late 1990s that prompted the council to start seeking advice.

Councillors were soon advised the wall was unstable, and could collapse in the next big storm.

A new wall was built in front of it in 2004.

At the time council staff were clear further protection also had to accompany the wall.

They suggested that long-term, the installation of a $2.5 million artificial offshore reef, made of sand-filled sausages, to reduce the power of the waves could solve the sand erosion problems.

But they also said it would be several years before the council would be able to consider such a project.

A great citywide debate about what to do about the wall followed.

Engineer Maurice Davis, then of Duffill Watts and Davis, who prepared the initial beach report for the council, told a public meeting at the time a wall was not ideal at all. But because one had been built there at a time when no-one knew what effect it would have, and houses had long since been built behind it, the city was stuck with it.

A new wall would have to be built in the same place, as close to the old wall as possible.

Its negative effects could be alleviated by encouraging the deposit of sand on the beach and limiting the sand's longshore drift, he said.

As well as the artificial reef idea, people at the meeting also discussed other long-term options, including building a permeable or solid breakwater out from the headland and building sand-trap fences along the beach.

Duffill Watts and Davis eventually recommended the council build a 20m breakwater out from the St Clair salt water pool.

It is understood its plans were reviewed by other experts, who recommended the breakwater extend further than that, but when the council eventually applied for consent to build the sea wall, a 20m breakwater was included.

It was not a popular idea.

There was a strongly negative reaction from surfers, and a regional council panel declined to give resource consent for it based on the health and safety risks it posed to surfers.

The panel was also concerned the breakwater would project into a known channel used by surfers and affect wave breaks and currents in an area that was so important to surfing.

''We consider that the value that a readily accessible good surfing beach offers Dunedin must be preserved. The rock groyne would be inconsistent with the classification of St Clair beach as a coastal recreation area,'' its decision said.

In 2005, a report for council prepared by Duffill Watts and King on damage to a sea ramp on the new wall raised the issue of the breakwater again.

It said the wave conditions of the previous six months and the ''dramatic degrading'' of the beach provided a sound argument for the council to reconsider the project.

The beach profile was ''seriously sucked down'' and there was little sand protecting the base of the wall and ramp, director Barry Chamberlain told councillors.

It was left to staff and a council consultant to consider the groyne suggestion.

It seemed to fizzle out.

In 2007, the council commenced a substantive investigation into stabilising the city's beaches, following storm damage to dunes at Middle Beach.

Submissions reflected concern from the community about the sea wall's effect on erosion at St Clair Beach, and support for an artificial reef to solve the problem again came through strongly.

At some point, the council suggested taking sand from Tomahawk to replenish St Clair and Middle Beaches, a plan abandoned after Tomahawk locals did not take kindly to it.

From the investigations came the long-term Ocean Beach Domain Management Plan.

Adopted last year, it says the area in front of the sea wall is managed by a separate city council process and proposes no action for the area other than maintaining the sea wall.

The nature of that ''separate process'' is unclear, although parks and recreation manager Mick Reece said it was related to the consent, which says the wall shall be maintained in good repair throughout the 35-year term of the consent.

Chairman of the hearings committee Cr Colin Weatherall said St Clair Beach was out of the project's scope.

''It was always going to be the difficult quantum, but we never envisaged what's happened there now.''

Last week, he asked council staff for a report as soon as possible.

If everyone said the sand migration issues needed to be addressed, why has it not been done?It seems the reasons are complex.

The answer would require a close reading of dozens of reports, studies and assessments on the matter done by council staff and experts over the past 15 years.

There have been changes in councils and council staff.

The man responsible for the sea wall now is transportation operations manager Graeme Hamilton, who says he inherited the sea wall from the council's parks and recreation department 18 months ago.

Parks and recreation inherited it from the city architect/city planning department, which dealt with it when the wall was replaced.

Mr Hamilton's focus is on fixing the immediate problem: stopping the Esplanade from slumping any more.

He has not thought too much about sand yet.

''If the wall was built on rock, there wouldn't be an issue with sand.''

The long-term options for sand retention would be determined and reported back to the council for a decision, he said.

At this stage, it seems councillors will not receive that report until September, as it will not be ready for the next committee round in July.

Cr Paul Hudson, who was on the hearings committee which dealt with submissions on the 2008 sand investigations, said the whole area was part of those discussions and councillors were well briefed on issues along the coast, including St Clair, as part of that.

It is not that nothing has happened to try to divert the sea's energy at St Clair; work such as dumping stones at the foot of the wall had taken place from time to time, he said.

It seems likely the council may now have to seriously consider doing something about the sand situation.

And that will come back to money, of course, of which there is not much to splash around.

The 2004 sea wall and Esplanade was originally to cost $3 million and ended up costing about $7 million.

The cost of another major project is unlikely to be something any council, especially one in a tight spot, will welcome.

Any options involving more rocks or structures on the beach or in the water are also unlikely to be popular.

But perhaps people will have to accept it could well be a choice between some effects on the amenity - visual or otherwise - and no beach at all.