Erosion and accretion is a natural process, the Otago coastline has been in constant fluctuation for millions of years. Merely 7 thousand years ago the sea level was much higher than now and the peninsular arm was an offshore island. Even back in the 1800's the peninsular arm was only joined to South Dunedin by a sandy isthmus.

What we are faced with now is the issue of maintaining some kind of equilibrium to protect the man made assets that were placed along and inshore of our coastline in the last 160 years from this natural process.

Where did it all go wrong?

I am no expert at all, but following my natural curiosity I have my theories based upon stacks of research.

1/ Before the white man came to Dunedin, the now almost straight stretch of beach from the salt water pool to lawyers head (Ocean Beach) was an indented sandy bay which reached about 800metres further inland, this was created by the natural offshore morphology in conjunction with the landforms at shore along the coast.

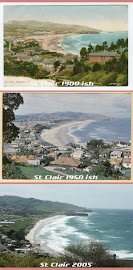

2/ .. white man settles in Dunedin.. and after a few decades decides that he needs more land for settlement and begins the process of land reclamation through the draining of the swamps from South Dunedin to St Kilda, the sand mining of the dunes for harbour land reclamation and subsequent development over the previously sandy bay. This occured over 90 years from 1860 to 1950 when most of the 'reclamation' was completed.

3/ During this time, ongoing and prior, a cyclic natural weather phenomena occurs in 7 to 13 year cycles where natural storm events cause heightened erosion along Ocean Beach. Some storm surge events thrust seawater inland as far as Hillside Road (2ks inland) inundating homes and businesses. Two prior hard rock sea walls were destroyed and the esplanade was washed away completely during one storm event. So began mans battle with the ongoing issue/need for coastal protection, and the implementation of various engineering solutions.

4/ The extensive land reclamation within the previous sandy bay area caused a complete destruction of the natural dune system, which had previously found equilibrium as a self healing system over thousands of years. (actually when Dunedin was first settled, there was only a sandy isthmus joining the peninsula to the mainland, and the flat area of south Dunedin and St Kilda and parts of St Clair was swampy uninhabitable land which was laboriously drained by the market gardening Chinese immigrants).

4a/ After the 1950's periods of effective 'soft engineering' sand stabilisation methods such as sand trap fences gave a reprieve from erosion issues for many decades. After the Ocean Beach Management was handed over to the Dunedin City Council in the late 1980's these methods were disbanded and the erosion issues resurged.

5/ Bring on in 2002 the redesign of the new sea wall at the St Clair end of Ocean Beach. Due to adjustments in its positioning the solid structure created seemingly subtle but critically ongoing changes in currents causing deep erosion of the sandy beach along its base and drastically lowering the beach profile. This placed stress through exposure of the toe of the reconstructed dunes at the end of the sea wall [with whats called an 'end wall effect'] stripping sand and exposing the sand sausages from beneath the dunes.. these sausages (placed as a means to protect the dunes from erosion) then became hard/end wall themselves. and forced the erosion further up the beach as an end wall effect into middles beach to soft dune.

5a/ there is also the possibility that the construction of the bridge/pipe for the sewer outfall placement has been causing disturbances on the nearshore currents which have amplified the erosion.

6/ Then bring on another natural cycle of a series of strong south east swells/storms during June and July this year which caused the lowering of the beach level/profile even more allowing the storm surges to attack the toe of the soft dunes.. causing 8-10 metres of dune depth to be washed away over this 6 week period.

The beach is now in a 'self heal mode', where banks have been naturally created offshore which act as a buffer to incoming swells so the wave energy is dissipated and does not effect too much the eroded dunes. In the past this process allows the beach profile to slowly raise allowing recovery of the dunes by creating a higher dry sand beach again, this dry sand blows onshore to reform fore-dunes, the eroded dunes naturally re-profile and re-grassing occurs, the dunes and beach heal.. Unfortunately it is not at all possible for a self heal to occur here as would have been the case pre-settlement, as the natural profile and function of the dunes has been destroyed.

So its up the the city council to research the best possible way to allow the beach to recover and the dunes to heal ( with help from hundreds of hours of digger work to remove hard fill used in the 50's for reclamation).

I just cross my fingers that they do their homework and take a look at the more natural processes that they have been alerted to [such as Holmberg] that will allow a process to be installed where nature is worked with in conjunction with human intervention.. it is very possible, and is proven overseas.

the dunes must also be allowed to encroach back landward into the reclaimed parks areas so at least some degree of self healing is possible.

we face the truth that the problem is 'man made, aided by nature', so the solution should be 'natural, aided by man'.