ODT By

David Loughrey on Wed, 14 Apr 2010

Differing views have emerged on the possibility of saving low-lying areas in southern Dunedin from sea-level rise.

Consulting engineer Dave Tucker yesterday said engineering solutions were available to deal with the issue, while Sustainable Dunedin co-chairman Phillip Cole, also an engineer, said a retreat from the area was inevitable.

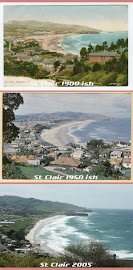

A report released on Monday identified South Dunedin, St Kilda and St Clair as "hot spots" vulnerable to what could be a 1.6m rise in sea levels by 2090.

The report on the effects of climate change in Dunedin was commissioned by the Dunedin City Council, written by University of Otago Emeritus Professor of Geography Blair Fitzharris and released on Monday.

It said the city would eventually have to protect, retreat or evacuate areas including South Dunedin, St Kilda and St Clair.

Other problem areas were the harbourside, the lower Taieri Plain, including the Dunedin airport, populated estuaries along the coast, and the ecosystems of upland conservation regions.

In his report, Prof Fitzharris said the city needed to focus on "adaptation" to deal with the problem, and that was not a one-off event but a process that involved awareness-raising, the development of knowledge and data, and risk assessment.

Some adaptation was occurring on a limited basis, he said.

"However, there remain significant challenges to achieving concrete actions that reduce risks."

Implementing measures such as planned retreat and dune management, building design, prohibition of new structures and siting requirements that accounted for sea-level rise was difficult.

Mr Tucker has previously told the council it needed to form long-term mitigation strategies to deal with the effects of climate change.

Yesterday, he said two areas of Dunedin were not protected by hills: the St Clair and St Kilda beaches area, and the lower harbour near Port Chalmers.

The areas of risk if the sea came through were not just South Dunedin, but all the reclaimed land in the city, including land up to the Dunedin railway station, and up to parts of the University of Otago.

He suggested a "barrage" across the harbour that would take advantage of a natural bottleneck between Port Chalmers and Portobello.

The barrage would link Goat and Quarantine Islands, trapping water in the upper harbour during high tide and releasing it at low tide. That would deal with sea-level rise at the harbour end of the city, and could include turbines to produce electricity.

The beach end of the city "could be saved in some engineering manner".

"You only need to go to Holland," he said, where technology had been developed to keep the North Sea out of the country.

"I'm quite sure if you got consultants from Holland they would come up with ideas to stop sea ingress."